Holiday

1960

For

our holiday in 1960, we decided to see Kashmir. After flying to Calcutta,

we boarded the third-class air-conditioned express for Delhi. We had Judy with

us at six months old. The trip took 24 hours, and we had to spend the day at

the retiring-room at the main railway station in a temperature of 112

Fahrenheit, drinking lots of water and trying to keep cool until our next train

left in the evening.

In the evening we left Delhi on

the Pathankot Mail for the north-west. Overnight we travelled towards the

mountains and the Pakistan border so that by morning we reached the railhead at

Pathankot, right where the plains meet the steep ascent to the Himalayas.

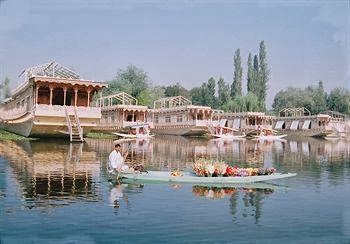

Dal Lake in Srinagar

|

We transferred to a bus and started our journey by road. The bus followed the bottom of the hills to

the north-west again for three hours until we reached the city of Jammu. For

this time we had had the mountains to our right and the Pakistan border on our

left. We occasionally saw camels, but most of the country was dry and dusty,

with almost no sign of people.

At Jammu we entered the walled city and drove through the winding,

steep, narrow streets of the town. The road continued uphill for hours and then

descended into a huge river valley. It clung to the side of the mountains, with

gangs of workers repairing and upgrading the road all the way. Every so far

there were slips and washouts.

Before long we turned north and began to climb again, until by evening

we reached the town of Banihal, where we stopped at the Dak bungalow for the

night.

In the morning we climbed for a few minutes more and then entered the

Banihal tunnel. On the northern side we came out into bright sunlight, blue

sky, and a 360 degree panorama of snow-covered mountains. Enclosed by the

mountains was a huge valley of green grass, poplar trees and wild flowers:

Kashmir.

For the rest of the day we trundled downhill and across the floor of the

valley to the capital city of Srinagar. There we took a taxi to the ghat on the

edge of the Dal Lake, and then a shikar (gondola) to a houseboat across the

lake for our first week’s holiday.

The houseboat was like a motel on a boat, permanently moored with other

houseboats, where we lived for the four or five days we stayed in Srinagar,

exploring the city.

Probably the highlight was our visit to a carpet factory,

where we saw three workers sitting on a bench with a vertical frame in front of

them, weaving the carpet pattern and singing all the time the pattern they had

memorised.

After our week in Srinagar, we climbed aboard a bus for the trip up

country to Pahalgam, where we lived in a tent in a camping-ground for the next

three weeks. Each day we would explore some of the little town and the

surrounding country. The highlight was

our trek up the valley as far as the snowline, where there was an ice bridge

and the beginning of the trail up to the popular Hindu pilgrimage destination

of Amarnath.

We could have travelled more widely in Kashmir, but having a six-month

old baby with us restricted us.

The journey home was uneventful; we spent one whole day in the bus

driving down to Pathankot, where we slept on the station platform with hundreds

of others waiting for the Delhi Mail first thing in the morning. This time

there was no long wait in Delhi and soon we were on the air-conditioned third

class express speeding to Calcutta and the plane home.

.png)